The PR (Proportional Representation) Conundrum

The smoke and mirrors of PR look good, but make matters worse.

Perhaps a good place to begin would be to provide some sort of definition of PR or describe what it ought to be as opposed to what it really is.

Our parliamentary elections are a collection of 650 local elections run on the principle of winner takes all. The summation of all the winners leads to one party having the most candidates elected and often sufficient to outnumber all the other parties put together. Sometimes, but rarely, that doesn’t quite happen, and coalitions are pursued. The former of these two possible outcomes allows majority government to reign unopposed for the next parliamentary period, but the second one, although trickier than the first still has majority government as an objective but needs a combination of concession and bribery to reach that goal. Under this format most people’s votes do not count at all, as the 2019 general election will testify to, when 26,495,911 votes out of 32,014,110 votes did not count towards the establishment of an 80-seat majority government.

This quite odd situation shows that it isn’t votes that count so much as how they are organised. At constituency level the futility of voting is more starkly defined. In 2019 in the constituency of Folkestone and Hythe 44,858 votes would have been more useful on the fire than in the ballot box. That number also included 21,000 Conservative votes, which were over and above the 14,147 votes needed for the Conservatives to win and counted for nothing at all. You might think that such popularity should at least count for something, but no.

What the system does do, however, is very successfully shut out any opposition to the Labour or Conservative parties, which suits them both very well and is why the present system will not be willingly changed by them.

OK, so the background of the desire for PR is based upon a belief, which I share, that we are more likely to be better represented and have better government if our governance was more widely supported. I would add to that, the need to limit government power, and the way it is so narrowly focussed on the Prime Minister, and to create a structure that offers opposition some teeth. I don’t mean the pantomime of opposition we get now, but thoughtful and meaningful checks and balances.

The concepts underpinning what most people believe PR to be is a mechanism that more evenly shares parliamentary seats and where each seat requires a similar level of support. There are many systems that purport to do this, but they all have the same problems.

1. The establishment of an all-powerful parliamentary majority is still the objective even though that concentration of power leads to corruption.

2. The calculations simply end with seats, and no thinking occurs beyond that point. The reality is that whilst seats may be more evenly distributed, the exercise of power goes in quite the opposite direction.

PR systems only aim at seats, whereas it is the exercise of power that should be more proportionally distributed.

To illustrate how this happens in a real-world example, let’s take a look at that bastion of proportional democracy, Sweden.

Sweden elects its members of parliament on a nationally and fully proportional system. There are constituency areas, but Swedish politicians don’t have the connection with their voters that UK politicians do. In a system such as this, the suggestion that you could walk in and see your MP with a personal issue is quite alien. They look at you in askance for suggesting such a thing and the general acceptance in Sweden that their politicians are simply out of reach is something that has long standing cultural roots. In the UK we quite like the constituency link, despite the fact that it’s a bit of an irrelevance for most of us, but it is there, and our MPs do like to big it up a lot.

So, lets look at the last Swedish election and their current parliament. A national proportional system does have to have some sort of bar, obviously a certain level of support is desirable and in Sweden it’s arbitrarily set at 4%. It is, of course, an election for parties only, in practice like ours, and a party has to get 4% of the vote to get a share of seats. So far so good. But then it all falls apart.

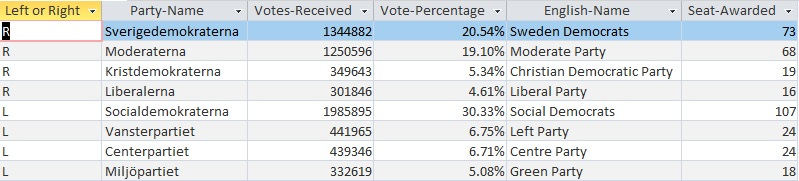

As it happens, in the 2022 election, eight parties achieved that 4% hurdle, and eight parties are represented in the Riksdag (Swedish Parliament). As it happens four are on the left and four are on the right. Here’s how the votes fell.

The first thing you notice is that the Social Democrats with 30% of the vote get no say at all, because the summation of the left of centre parties fell three seats short of the right. That now has shrunk to two because a Swedish Democrat electee has left the party and now acts as an independent. However, the right coalition outnumbers the left coalition, so it is for them to form a government after the usual bun fight for jobs behind closed doors.

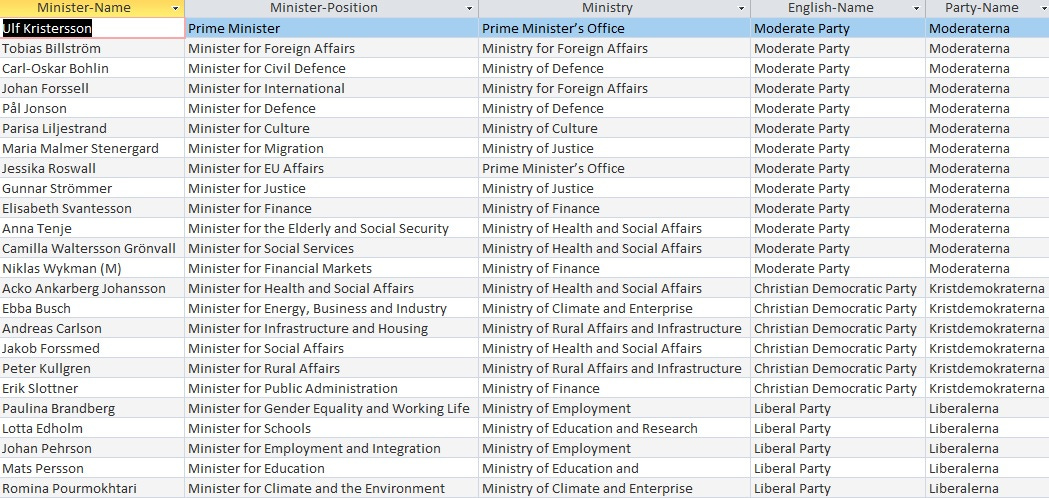

Here's how the ministerial positions were distributed.

Notice anything?

The Sweden Democrats, with 20% of the national vote have zero ministerial positions whilst the Liberal Party, with just over that 4% benchmark hold the power to determine policy in four ministries of state. The Christian Democrats with just over 5% of the vote hold six ministerial positions, so eleven of the 24 ministerial jobs have gone to parties whose combined support is still only half that of the Sweden Democrats, who have no ministerial positions at all. There is a massive difference between support and power exercised and this aspect of proportional voting is usually ignored. No, make that totally ignored.

So why is that. How can this be when the largest party, whose leader (Jimmy Åkesson) should be Prime Minister, wind up with zero ministerial power?

The reason is that the Liberal Party don’t like the Sweden Democrats in much the same way as our rump of a Liberal Democrat party with typically miniscule support wouldn’t co-operate with UKIP, for example. It’s quite extreme when a tiny party with tiny support can call the shots with the threat to abandon any notion of government. They have been well rewarded, nobodies with no support, get to show off their shiny new jobs.

PR often leads to minorities wielding far greater power than their support justifies and a huge reason why we should abandon any notion of doing it this way. There is a better option and I’ll elaborate later. For now, though, you must be asking yourself why the largest party in this coalition would allow the smallest to run the roost, and the answer is fascinating.

Jimmy Åkesson is nothing if not a smart cookie. He, and his party, The Sweden Democrats, forfeited ministerial power, the influence, the celebrity and attention that the great offices of state bring, to gain agreement for their election manifesto to be implemented in full. In essence, his offer was to forgo the jobs, but you have to implement our ideas.

How about that? Contrast such a position to our very own self-serving bunch of chancers, the Liberal Democrats, who did exactly the opposite. They sold out their supporters and their voters in 2010, just to get the posh jobs, and just so Nick Clegg could posture in that oh so pointless of titles, Deputy Prime Minister. It didn’t go unnoticed as they crashed from around 56 seats to 8 in one parliament but make no mistake, they would do exactly the same again.

For Sweden, things remain uncertain. A small majority is bad enough, but the fragility is enhanced by relying on the same sort of chancers as our Liberal Democrats who are happy to support the agenda of the Swedish Democrats in return for posh jobs. It shows their political opposition to be opportunistic only and, like the UK, the electorate will remember this when they next get the chance.

So, what to do. This link offers a fuller explanation:

My new book ‘The Living Vote’ shows how we can have fairer elections, much wider representation, no coalitions and an equalisation of power exercised which is much closer to the electoral support received. It’s to be published on 29th September 2023, so keep an eye out if this subject interests you.